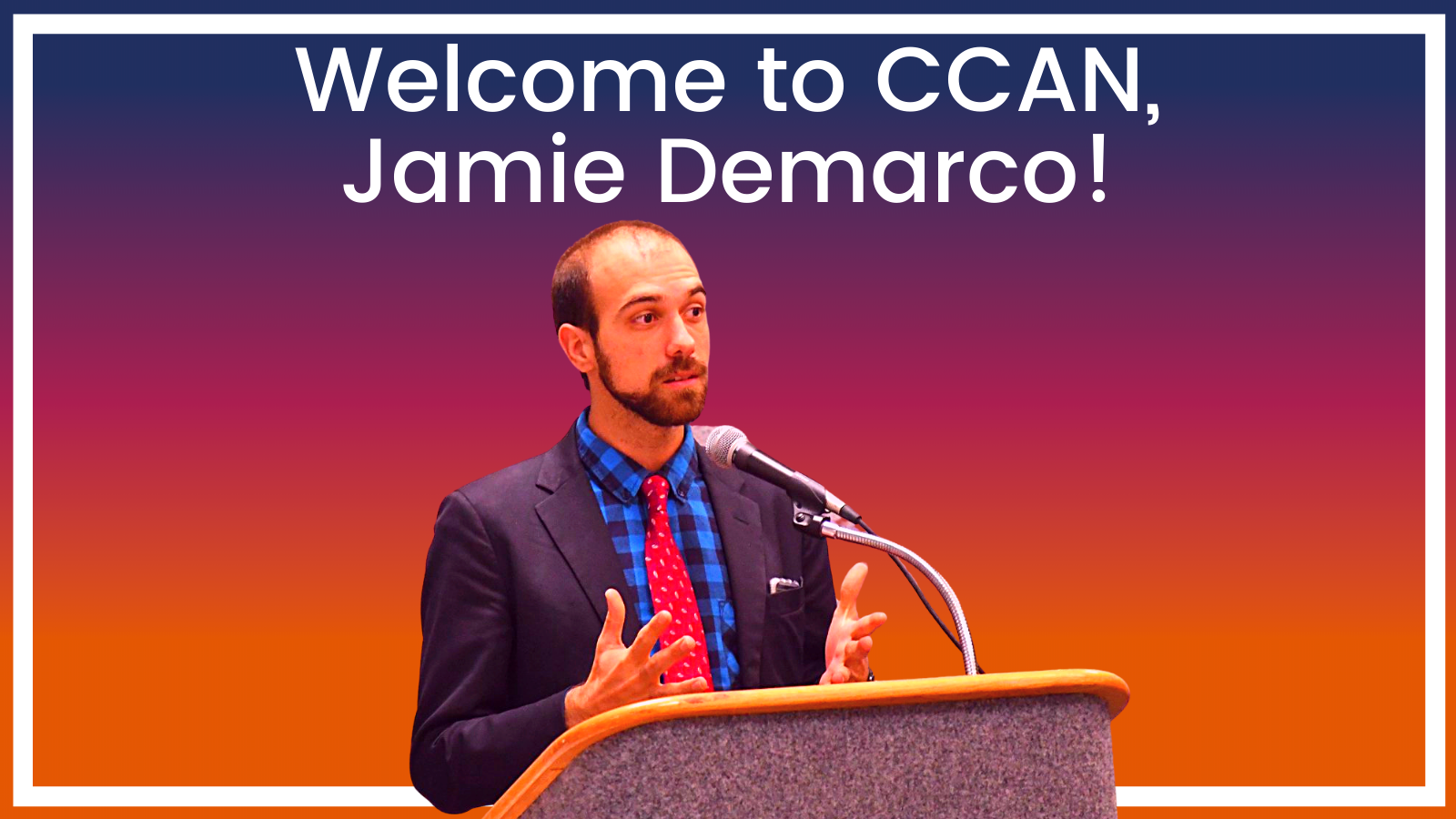

Denise Robbins has spent the past four years as communications director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network. Denise grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, went to college at Cornell in upstate New York, and has called DC home for the past eight and a half years. She first decided she wanted to save the world from global warming when she was just eight years old. She co-authored a book about climate refugees called rising tides, climate refugees in the 21st century, published by Indiana University Press in 2017 and is currently working on a novel and short story collection. I was lucky enough to have a chat with Denise before she passed the baton off to our new communications director.

Follow along with the transcript below:

Denise Robbins 0:40

I feel like I should start with how I started, um, which was right after Trump got elected. My final interview, my in person interview was two days after he got elected, so I just barely had time to like, get over this brief hangover. Um, and prepare for this interview and get to the office and meet Mike and meet Kirsten. And it was just insane, like mental space to be very somber, very, you know, shell shocked. And the interview, you know, the mood was somber, but like people are so you can be ready, you know, they were ready to take on Trump. They’re like, this is why we’re here. This is why we exist. It’s not just about wanting the higher ups at the federal level to wave their hands and solve climate change, but about building movements from the ground up. And continuing to do that and outpace the federal, especially during the Trump administration, my first legislative session in Maryland that the state legislators were similarly like, Oh, my God, we have to do so much. And Marilyn passed a ban on fracking. And it’s sort of it’s interesting, because we do kind of wonder if Trump hadn’t been elected, would Maryland have banned fracking? It’s, it’s hard to know. And we’re, it’s hard to even say that because I feel like just looking back, it’s almost unconscionable to imagine Maryland having fracking, but it was very seriously gonna happen. And it took a long time. And a huge fight to ban it. So I started at CCAN at the tail end of this seven year battle to ban fracking in Maryland, it started with a moratorium, it started with our organizers just going from city to city to county to county, and getting local bands. And I just was able to ride the coattails of that and just pass this incredible bill and my first legislative session, and it was such such a whirlwind. It was pretty incredible. I just recall specifically sitting in the conference room in our takoma park office, and Governor Hogan announced that he supported a ban on fracking. And it was like, what, like we were so not expecting that. But on the other hand, earlier that day, we had just gotten word that there was a veto proof majority of support for the ban on fracking for the fracking ban bill. So Hogan essentially had no choice. I mean, he at that point was like, I guess I should take credit for this, because it’s happening, whether I like it or not, a few have vetoed it. That would have been overturned. But it was very, you know, itself just to like, Oh, my God, it’s actually happening. And I think everyone kind of freaked out. I think somebody bought a bottle of champagne. And I think most of us were just like, No, no, no, we have too much work to do, we have to do all this work. And then Mike, just being like, hey, like, stop for a minute. And enjoy this. Like, we got a ban on fracking in Maryland. And, um, and yeah, so that was just, you know, the first couple of months of my time at sea can. And in the next four years, we passed an amazing bill, a clean energy bill in DC, we passed another really great clean energy bill in Maryland. And then finally, an amazing clean energy bill in Virginia, like all the big three, the Atlantic coast pipeline was rejected. All of our other pipeline battles have so far, none of those pipelines have been built any and all of the pipeline battles that I’ve taken part in, none of those pipelines have been built. So it’s been a while you look back at our CCAN’s work, you know, federal landscape aside, and absolutely incredible for years.

Charlie Olsen 4:48

Can you tell me about some of the lessons that you learned from that first victory and how you use those in the campaigns that followed?

Denise Robbins 4:57

Yeah, so I think when it came to the ban on fracking. It was very clear, first of all, that this was a totally grassroots up from the ground up campaign, that it would not have happened if there weren’t so many localities that were educated and over the span of so many years, changed their minds about fracking Marylanders used to support fracking. And that was just a long time of education to switch that. And then, you know, eventually getting to a point where most people in Maryland didn’t want fracking in the legislator, legislature needing to respond to that. And so I think that, you know, first of all, it was just a really great way for us to learn how to reach out to a whole state around one campaign and get more people involved. And, and build on that to pass forward looking legislation, you know, not just to always be fighting against fracking and to be fighting against pipelines, but to be fighting for solutions, like clean energy,

Charlie Olsen 6:09

The next major campaign after that the passing of the Clean Energy DC act, what did you learn from that?

Denise Robbins 6:16

The really great thing about that, for me was just, I live in DC. And it was, this is what democracy is, you know, getting to like, see the legislature legislator who represents me and witness the dozens hundreds over the course of the campaign, probably thousands of DC residents, you know, come into the DC council building and lobby their legislators and build a strong movement toward to where DC council just simply had to pass an amazing bill otherwise, we wouldn’t have gone away or left them alone. And it was that that was really cool. You know, it was I learned a lot that lobbying really just seems um, having I guess, I don’t know what lobbying means. Anyone can lobby, you know, any your neighbor on the street, your grandma can lobby like anyone can be a lobbyist. In fact, it’s a much more powerful way to express your voice to your legislature, to your legislator than voting, for instance, it’s much more direct and pretty cool. And this particular campaign was great because it just brought so many organizations around DC together to support and pass the Clean Energy DC act and weren’t forced to make a lot of connections. So that you know, a lot of these organizations still coordinate, we still have a coalition called the DC Climate Coalition. And I’m still pretty, you know, active and involved in DC politics just because it’s my home.

Charlie Olsen 8:00

What was your favorite action that you coordinated for that campaign?

Denise Robbins 8:05

Oh, there was like, a, such a fun action that we did, which involves playing volleyball at the unfreedom Plaza right outside the council building. And oh my gosh, I don’t even really remember. I think we were like, We needed it to pass. We were like we had done all the work, basically. And we’re just waiting for the council to hold a vote and pass it. And they were gonna delay it and not have it happen in 2018. And then, of course, there was a heatwave, because there’s always a heat wave, you know, once a month in DC, in October and November and so it was very warm. And we got everyone out to the freedom closet wearing like swimsuits and lifeguard outfits and like, erected these giant volleyball tents and had a humongous inflatable Earth and we were just batting it around. And it was just like, such a joyous day of action and and, you know, telling the DC Council, you know, stop playing games with this bill, pass it and, you know, so there’s some fun metaphors going on there. I specifically, you know, picked up the volleyball mat from somebody and I had to trudge like on a very rainy night in Ward five. I remember, but it was super worth it.

Charlie Olsen 9:28

The Virginia clean Economy Act is one of the strongest pieces, I believe the strongest piece of environmental legislation passed in the American South ever. Can you tell me about some of the lessons and takeaways from your work on that?

Denise Robbins 9:42

Yeah, the Virginia clean Economy Act is basically involved in the story of a state, you know, Virginia that was so rad for so long, and so far behind on climate and so many other issues that once the state legislature flipped to blue. They’re like, Alright, let’s go. They changed decades of history and their 90 day session. So the Virginia clean Economy Act, it was an amazing bill, it was still a really tough battle, you know, people pulling on it from all sides, it was just going to be a very big bill that a lot of people had a lot of steak and but, you know, ended up passing it and allowed Virginia to totally blow out of the water and come from the back of the pack to the forefront and local state climate policy, you know, even beating Maryland. So we have little internal sea cam competition there. Um, but yeah, that was that was incredible. It’s, it’s kind of funny. The session ended just in time before the COVID lockdown. I was in Richmond on those final days, and people were just starting to like, joke about like, oh, should we not walk, shake our hands? Or should we do the elbow bumps? I don’t think it has been spotted in Richmond yet. But the lockdowns began just days after the bill passed. And you know, for instance, and Marilyn, Marilyn, could have kept pace with Virginia barely, they’re probably going to pass another really good climate bill. But the legislative session ended super early. And so they weren’t able to pass it. So at least we have some more to look forward to in Maryland this spring.

Charlie Olsen 11:36

Looking back on all of the campaigns that you’ve worked on, for the past four years, are there? Are there any moments that you would go back and change or anything that you would want to do differently on those campaigns?

Denise Robbins 11:48

Not really, I don’t know. I think the biggest thing that I would want to do differently is just not be so stressed out. I feel like, you know, saving the climate is pretty stressful. And we work really hard. And I just wish I had had a little bit more mindfulness, I guess, and just been able to not let myself get stressed out over over all the things and just go with the flow, and do what I needed to do

Charlie Olsen 12:18

In the past four years since the 2016 election, Can you tell me a little bit about how the climate activism landscape has changed in that time, from your perspective?

Denise Robbins 12:31

Night and day? I think that there’s so many more people who not only care about climate change, but really understand the urgency and want to get involved. I mean, four years ago, yeah, people just didn’t really join the big climate marches and things like that. And then well, first, the IPCC, the United Nations. In our panel, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, released that report that said, we have 12 years, you have 12 years to solve climate change. I was actually on vacation at that point. I was in Scotland for a friend’s wedding. And I saw newspapers in the airport with that number like blasted all over the front of the front page of these newspapers across the Atlantic Ocean. I was like, Oh, my God, like, whatever it is about this one particular report, like, it’s really getting people to notice. And I, you know, it wasn’t actually new information for most people in the climate sphere. But for everyone else, it was like, Holy smokes. I’m so gretta fudenberg I believe, you know, came out of reading that report and decided to start her amazing inspiring school strikes and inspired millions of people across the world. I mean, the school, the strike, the climate strikes, that happened globally. That was like nothing else I’d ever, ever witnessed. And that was incredible to be a part of,

Charlie Olsen 14:15

What about the school strikes? Like your experience with them? What about them brought you inspiration?

Denise Robbins 14:22

In general, it definitely was inspiring to see so many young people really getting involved and passionate. I just sort of wish at that age. I mean, I have cared about climate change since I was eight. But I would never have joined a protest when I was in elementary or middle or even high school. I just think that it’s amazing to see an entire generation that is now willing to go out of their comfort zone. And really speak up for what they care about and what they’re concerned about. Yeah. Well, between sunrise and Alexandria, ocasio Cortez, and introducing the idea of the green New Deal. It was sort of the first time that there is such a strong message of hope. And it’s so hard to just be, you know, Doomsday all the time. And it’s just so nice to have this breath of fresh air of hope. And I think sunrise and AOC made that

Charlie Olsen 15:28

AOC in the intercept that video about what the future could be, I have that saved on my phone. And I sometimes just go back and watch it when I’m needing to pick me up as a communications director, like your position is heavily focused on like the media and climate media. And I think the question that I’m really curious about is like, how over the past four years, have you seen the media landscape? In reference to climate change?

Denise Robbins 15:53

change? Yeah, that has definitely also changed a lot before see Can I was actually working at media matters. So I was very clued in to how people in the media were talking about climate change. And they pretty much either weren’t talking about it, or doing this whole false balance both sides ism. That’s just so silly. It’s like having someone give the other side of gravity like, is gravity real? Who can tell? I couldn’t explain gravity, but I don’t question it. Yeah, I think, um, definitely, you see people talking about climate change more in the media, you actually start seeing people make the connections between extreme weather and climate change, which I think is huge. And I’m finding that both sides are still there a little bit, but it’s definitely gone down a lot. And I know that it was a little complicated for some journalists, because on the one hand, like, you can’t just not say talk about what the president says. And that was our biggest climate denier of all. But, you know, there’s a way to report on what the President was saying without necessarily just blanket repeating lies. And so I think that was a big learning curve for the media over the past four years, and the hope that the lessons they’ve learned apply to climate coverage going forward to can you

Charlie Olsen 17:26

Tell me about one of what has been your favorite part about working at CCAN, for the past four years? Aside from the whole thing? I’m sure

Denise Robbins 17:33

I know. Right? Um, how do you mean, it’s hard to just not say the wins. I mean, it’s just so it was so needed to have to have victories to have progress. And during the Trump administration, so it just allows you to fight for something and then enjoy it, when you succeed, I think it is kind of huge. And aside from that, I mean, the people at CCAN, people that work that you can over the past four years, and currently are some of the smartest, most passionate, funniest people that I’ve ever met.

Charlie Olsen 18:16

So it’s, you mentioned the wins, and I think that those are super important. And aside from those, working on climate is really tough. Like, it’s really hard, it is an existential issue. How do you stay grounded? How do you find yourself back to some semblance of calm or peace?

Denise Robbins 18:39

In a certain sense, there is a willful ignorance that’s almost required, like I, intellectually and theoretically, understand all the crazy drastic implications of climate change. You know, I’ve studied this for many, many years. But I on a day to day level, like, I just don’t really have the brain space or mental space to allow myself to really feel that, um, and I couldn’t I mean, I just couldn’t keep working if I did. Um, but every, every so often, it’s definitely, you know, like, when the people’s Climate March came through to DC, I think I found myself crying in the middle of that, and I couldn’t really understand why I think at that, at that point, just in the middle of this beautiful, super hot day, protest, marching through through the streets of DC it was just so moving. I was just like, so happy to be there and, and fighting for this thing that I’ve cared about since I was eight years old. So I think you know, you have to give yourself space to feel the climate crisis every once in a while, but aside from that, I mean You just gotta focus on what you can, what you can do and just keep working. And I will also say that a huge for me has just been writing, you know, I, you know that I love writing and especially writing fiction, and I get up every single day before work to write, and it’s just one thing that really helps get me through just being able. I think that’s, that’s the time of day where I give myself space to process. Um, and it’s in a way that I can like, sort of control.

Charlie Olsen 20:33

You are leaving to spend a year off writing a novel, I believe? Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Denise Robbins 20:45

Yeah, I would love to. I’m so excited. Not Not till you see can but to spend this year writing. Um, yeah, I’ve been planning to do this for a really long time, several years now. Sort of as an alternative to grad school. I was thinking about doing an MFA program. So now I’m just doing my own kind of MFA program, I have this huge list of things I want to read and things I want to write. I have a mentor who’s going to give me assignments, I’m going to be taking lots of workshops and classes. But yeah, I actually have already drafted a novel. And I’m, it’s currently in the email inbox of an agent who said that he would look at it, but Fingers crossed, but that’s, you know, we’ll see what happens there. But I just have so many other things I want to write. I have all these short stories and new novel ideas. And it’s really, I’ve actually found in the past couple of years that what I really love writing about fiction is climate change. I love writing about the solutions to one, you know, short story collection thing that I’m working on, of just all these different options there are and all these different, like really cool technologies and, and just how people like to react to that. And like their complications, there’s just so much material and art available, and when you get deep into the climate change world. And it’s another way for me to keep hope in, in my life.

Charlie Olsen 22:29

that’s super interesting. I’ve never met anybody who’s written fit who’s like written climate fiction. And I think that that is like a super, like, needed area of art. And I’m super excited to read whatever you produce. Is there a specific climate story that you’re interested in telling? I know, you mentioned, you like writing about solutions.

Denise Robbins 22:57

There’s one story that I find, like, so amazing. It’s this pair of Russian scientists who are working to re-engineer mammoths to basically turn elephants like give them more fur so that they can survive cold weather, and reintroduce them to the tundra to try to recreate Ice Age conditions. And they’re doing this so that the elephants can tamp down the earth and help keep the permafrost from melting. And so there’s this whole ecosystem, they’re trying to recreate and bringing amis to help recreate it to help, you know, prevent one of the most devastating feedback loops of global warming. And I just found that story so freaking cool. And like magical. That Yeah, I did. I wrote a short story inspired by that. And it just sort of like dials the magic up to 11. But that’s just you know, one, one example.

Charlie Olsen 23:57

That is really cool. That is like, really crazy. Could you tell me some of the one of the weirdest things you learned while at sea? Can the strangest, wackiest experience or thing that you have come into contact with?

Denise Robbins 24:14

Yeah, I think all of the weirdest stories are just about how weird politics can be. And I can’t even imagine what it’s like on a federal level. But on the state level, I mean, there are just some serious high jinks. My favorite is when we were supporting the clean energy jobs act in Maryland. And there was this vote, this committee wanted to vote to destroy it, or what’s the word to make sure that it wouldn’t get voted on at all that year. And the saving vote that blocked this vote that would have taken it down was a republican named Rick and polyuria. And so he voted in favor of the clean energy jobs act essentially. And he did that because of the offshore wind provision, which would result in more offshore wind turbines outside Ocean City. And one time he got a DUI in Ocean City for driving drunk. And he’s like, had a big beef about that. So he just like, voted for this bill to stick it to Ocean City.

Charlie Olsen 25:25

That’s so petty!

Denise Robbins 25:25

It’s so funny. It’s obviously not the best part of politics or anything. But is it was so funny,

Charlie Olsen 25:32

I loved it. If you could go back in time, until 2015. Denise, anything, what would you tell her?

Denise Robbins 25:40

I think, yeah, just don’t stress out. Just enjoy it. It was, um, I would say, Denise, you’re going to learn more than you can ever imagine. And then I would probably turn into a unicorn and like, jump off into a cloud or something. Because we’re talking about the theoretical here.

Charlie Olsen 26:08

That’s an interesting take on it.

Denise Robbins 26:16

You’re messing with like, I can time travel then like, what else can I do? I can become a unicorn.

Charlie Olsen 26:22

I was thinking it’s more like back then depending on your time travel mechanism. Is it like Back to the Future? Or is it Doctor Who time travel? Like, can you interact with your past self?

Denise Robbins 26:34

I think Well, yeah. Well, then I would go even further back, obviously and kill Hitler. Good, because who wouldn’t do that?

Charlie Olsen 26:41

Okay, that’s Yeah, true. I would have a hitlist Hitler would be on there. But like John D. Rockefeller, be pretty up there.

Charlie Olsen 27:01

Speaking of time travel, could you tell me who your hero is? Who do you look up to in the past and present, future even?

Denise Robbins 27:11

Yeah, I think right now, um, I don’t really know if I have heroes per se. But somebody who I really admire right now is a podcast host actually, named David naman. Um, he runs this podcast called between the covers, and he brings in authors to talk about their books and just like asks these really amazing, insightful questions. And I actually listened to an interview with him in Jennie to feel about this book about climate change. And it was like, such a beautiful interview, and I don’t know something about how he will bring in politics into like this literary space and have that be the norm. I really admire that. And, you know, I kind of am nervous about going into a writing world and feeling disconnected from the present day reality by I think he can show you how all of these politics and art really aren’t disconnected at all, and bringing them together. So I think that’s really cool. I will also say that Bill McKibben is a big, big hero of inspiration of mine, ever since college ever since he convinced me to go to DC and get arrested for the Keystone XL pipeline. And also, he’s just an amazing writer, like he is a beautiful writer, and has done amazing work. And that’s very inspiring.

Charlie Olsen 28:42

Being a communications director is a big role. I’m not sure how big from what I’ve seen of your work, it seems like you’re all over the place working on it. Do you have any tips and tricks for managing at all?

Denise Robbins 28:59

Oh, really, really, really good to do list? Honestly, that’s like, pretty much the only thing. Paper digital, digital, Oh, God, not paper. Now you have to be able to cut and paste and x things out. And yeah, I definitely learned so much about, you know, strategic time management and planning and all of that. And, and there are lots of spreadsheets that we have for references. We have so many planning documents. But at the end of the day, like all I have is just this one like digital to do list and that’s what gets me through. If I need to do something, and I don’t write it down, it’s not going to get done. So always write things down.

Charlie Olsen 29:50

I have learned that the hard way over time, I’ve learned that the hard way. That is a good tip. Final question: you’re going to take You’re off, you’re going to be writing, putting together your own MFA program. What’s next for you in this is you’re turning the page on this chapter of your life and going into the next key. Tell me a little bit about what the future looks like.

Denise Robbins 30:15

Not quite sure if I think part of it depends on how this next year goes. Um, I’ve honestly never really planned more than a couple of years ahead. I’ve always just realized what is the next best step? What’s the next right step?

Charlie Olsen 30:33

Thank you so much. Thank you for all of your contribution sissy can and to the climate movement and everything. We wish you the best of luck.

Denise Robbins 30:44

Thank you and I to you as well. I’m definitely excited about the crew that’s there right now. And we have a lot of a lot of good things coming and I’m really glad to have been a part of it.