Happy Black History Month, climate family! Black History Month is coming to a close, and I’m still fired up to talk about the incredible impact Black leaders have had on the environmental justice movement. Let’s dive into this crucial intersection of racial justice and climate action!

Black History Month is a time for reflection, remembrance, and celebration of the incredible contributions that Black people and communities have made to shaping our world. It’s also a time to critically engage with the struggles that continue to impact Black people, especially as they intersect with issues of environmental justice and climate change.

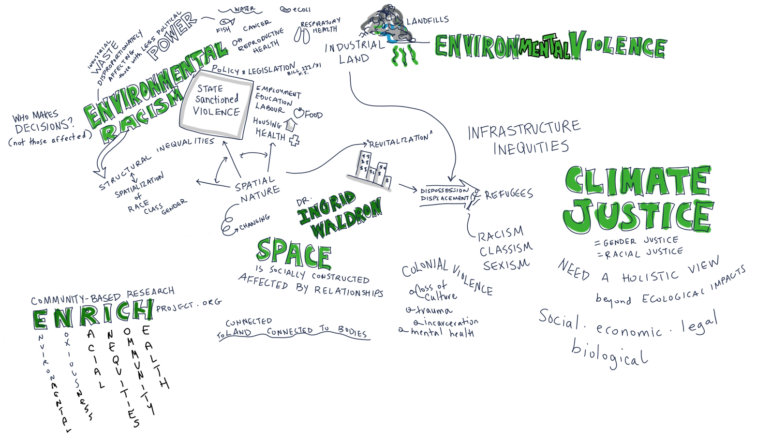

Environmental justice is not just about protecting the land; it’s about protecting people. Communities of color—especially Black communities—have long been on the frontlines of environmental harm. From toxic waste sites to polluted air and water, environmental burdens are disproportionately placed on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. This is the ugly truth of environmental racism, and it’s something we cannot ignore.

But here’s the thing: the fight for environmental justice is also a fight for liberation. It’s a fight against systemic oppression that harms the planet and its people. The negative impacts of climate change are often most acutely felt at the local level—where marginalized communities live, work, and fight for survival. That’s why we need to recognize the contributions of Black leaders in local climate justice movements and take action to support them.

The Roots of Environmental Justice

The environmental justice movement is deeply rooted in Black American history. It all kicked off in 1982 when the brave residents of Warren County, North Carolina, stood up against a toxic waste dump in their predominantly Black community. North Carolina had chosen to build a landfill for toxic waste in a community already facing economic challenges. The decision to place the dump there was approved despite the fact that the area had no history of industrial activity and was largely residential, with many families relying on farming and agriculture. This was not an isolated case but part of a larger pattern of environmental hazards being disproportionately placed in low-income, Black neighborhoods across the U.S.

The people of Warren County, led by local activists, such as Dr. Robert Bullard and Ben Chavis, refused to passively accept this decision. They organized protests, rallies, and demonstrations to resist the construction of the toxic waste site. For weeks, starting in September 1982, activists, community leaders, and residents engaged in acts of civil disobedience, including blocking trucks from delivering toxic waste to the site. Protesters were arrested, and many were subjected to police brutality, but their efforts drew national attention to the broader issue of environmental racism.

The Warren County protests highlighted how communities of color bear the brunt of our country’s pollution, and this fight signaled that marginalized communities would no longer silently endure this exploitation. Although the landfill was ultimately built in Warren County, the protests sparked a national movement that led to critical developments in environmental policy and advocacy. In 1987, the landmark report by the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice highlighted the disproportionate number of hazardous wastes sites in Black and low-income communities.

But the fight didn’t start or end there. Black communities have been battling environmental injustices for generations, from toxic dumping to air pollution. These struggles laid the groundwork for what we now call the environmental justice movement.

Environmental Justice and the Climate Crisis

The global climate crisis is here—and its impacts are catastrophic. From rising sea levels to extreme weather patterns, vulnerable communities are bearing the brunt of environmental destruction. However, the solution to this crisis lies in the same principles that have guided the fight for environmental justice for decades: respect for the land, equity, and the empowerment of frontline communities.

In the United States, Black communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation. Consider the history of environmental racism in places like Flint, Michigan, where lead-tainted water poisoned an entire city, or the continued struggles of communities living near industrial waste sites in places like Cancer Alley, Louisiana, where the risk of cancer is 95% higher than most of the country. The climate crisis amplifies these issues, making it clear that the environmental movement must center those who have been historically marginalized.

How You Can Help: Environmental Justice Organizations Serving Black Communities in the DMV Area

As we reflect on Black History Month, let’s also honor the environmental organizations serving Black communities and doing vital work on the ground. The following organizations are showing us that climate justice is about more than just reducing emissions – it’s about creating a fair and sustainable world for everyone. Support for these organizations is crucial, not just during Black History Month, but year-round.

If you’re in the DC, Maryland, or Virginia area, there are powerful organizations that need your support:

- Empower DC: Empower DC is elevating the cause of environmental justice to bring about improvements at the community and systemic levels. They are focused on DC neighborhoods most impacted by air quality issues.

- WE ACT for Environmental Justice (DC Chapter): Through advocacy, planning, and research, WE ACT is able to mobilize low-income communities of color to make environmental change.

Friends of Chesterfield for the 2025 Gas Plant Campaign Kick-Off Thursday, Feb 27, at the Central Library. - Labor Network For Sustainability(LNS) DC: LNS hopes to create a ‘just transition’ for workers and communities negatively affected by climate change and by industry transitions to renewable energy.

- Center for Community Engagement, Environmental Justice & Health (CEEJH) MD: CEEJH works to INpower fenceline, frontline, and underserved communities to resist ongoing environmental, climate, energy, and health injustices so everyone can thrive in just, equitable, and sustainable futures.

- CASA (Maryland & Virginia): CASA is a national powerhouse organization building power and improving the quality of life in working-class: Black, Latinx, Afro-descendent, Indigenous, and Immigrant communities.

- Friends of Chesterfield: Friends of Chesterfield is a community-based group in Chesterfield County bringing residents together in opposition to Dominion Energy’s proposed gas-fired plant in an environmental justice community.

- RVA Southside ReLeaf: Southside Releaf is working to tackle environmental injustice through hands-on projects, education, and advocacy in the Richmond Metro area.

- Virginia Interfaith Power & Light (VAIPL): VAIPL collaborates among people of faith and conscience to grow healthy communities by advancing climate and environmental justice.

These groups are fighting for cleaner air, safer neighborhoods, and a healthier planet. They are standing up against environmental injustices, advocating for policy changes, and empowering their communities to take action.

The Future Is Now

Black History Month is a time to reflect on how far we’ve come, but also to recognize how much work remains. The environmental justice movement reminds us that the fight for a healthy planet is inseparable from the fight for racial justice. In the words of the great environmentalist and activist Dr. Robert Bullard: “Environmental justice is a civil rights issue.” It’s time to honor the legacy of Black leaders who have been fighting for justice on all fronts and take action to support those leading the charge today.

Now, more than ever, the future of our planet—and our communities—depends on the power of collective action. Let’s ensure that Black voices and environmental justice communities are not only heard but supported in meaningful ways. Let’s commit to amplifying Black voices in the climate movement and working towards a just and sustainable future for all.